by Cécile Sykes, cecile.sykes@phys.ens.fr, Laboratoire de Physique de l‘Ecole Normale Supérieure, France

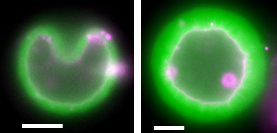

Simplistically, a living cell can be viewed as a bag filled with organelles and “cytoplasm”, a complex mixture of proteins. The bag consists of a membrane, a lipid bilayer that allows the passage of water and small molecules. Larger molecules are transported in or out of the cell by various active or passive membrane-embedded structures such as pumps and pores, or more complex channels of various conductance capacities. Cells are able to take up or release even greater volumes of material through endo- and exocytosis via the membrane.

Juxtaposed on the inner face of the cell membrane are networks of the biopolymer actin that are also present throughout the interior of the cell. This actin “cytoskeleton” ensures the dynamical and mechanical properties of the cell by assembling itself into semi-flexible filaments, i.e. with a persistence length comparable to cell size, about 10 microns. There is direct proof that the actin cytoskeleton can very robustly and reproducibly deform the cell membrane, and in particular, plays a role in the endo- and exocytosis of the cell (see, for example, references 1-4 in [1]).