Researchers from SoftComp partner CNRS-Montpellier and Paris, France, together with collaborators in Bangalore, India, have demonstrated that capillary waves can form at the diffuse boundary between two fully miscible liquids—something long thought impossible. In miscible systems, the composition changes smoothly rather than forming a sharp interface, so classical surface tension should vanish. Yet inside narrow microfluidic channels, where the liquids flow side by side, the researchers found that a brief, non-equilibrium “interfacial tension” appears because the concentration gradient between the liquids is still steep just after contact.

Why We Can Cut Rubber Easier Than We Tear It

11th December 2025

Water’s Hidden Switch: How Ferroelectricity May Trigger Its Mysterious Phase Transitions

17th December 2025

Why We Can Cut Rubber Easier Than We Tear It

11th December 2025

Water’s Hidden Switch: How Ferroelectricity May Trigger Its Mysterious Phase Transitions

17th December 2025

This fleeting tension drives a transition between two wave behaviours. At low flow rates , the two-fluid system shows an inertial regime, where the wave number (𝑘), which measures how rapidly the waves oscillate in space, does not depend on the wave frequency (𝜔). However, as flow rates are progressively increased the waves shift into a capillary-wave regime, where 𝑘 increases with 𝜔 following the classical law 𝑘 ∼ 𝜔²ᐟ³. This scaling usually applies only to immiscible liquids with a well-defined interface, which makes its appearance here especially striking.

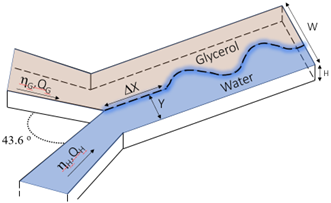

To observe these effects, the team used PDMS microchannels to create two adjacent streams of water and glycerol and recorded the interface at millisecond resolution. They identified two dispersion branches, meaning two distinct relationships between wave frequency and wave number. In the capillary branch (C), waves behave as if a true surface tension is present: higher frequencies go with larger wave numbers. In the dissipative branch (D), energy is quickly dissipated because of confinement, so the frequency becomes almost independent of wave number.

Two relaxation regimes revealed

The capillary branch made it possible to extract an effective interfacial tension—a measure of how strongly the liquids temporarily resist mixing. It drops extremely fast after contact, much faster than predicted by the widely used “square-gradient theory,” which models how concentration differences generate interfacial stress. The data instead match a more complete theory that includes higher-order gradient terms—mathematical corrections needed when concentration changes are very sharp. This theory reveals two relaxation regimes: an early stage dominated by steep gradients and a later stage where classical behaviour is recovered.

The study also shows that geometric confinement—the narrow width of microchannels—can strongly suppress capillary waves, explaining why previous experiments in miscible liquids failed to detect them. By revealing how transient interfacial tensions evolve on millisecond timescales, the work opens new possibilities for probing mixing processes in microfluidics, flows in porous materials, and systems far from equilibrium.

Read more: A. Carbonaro et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 054001 (2025), DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.054001

SoftComp partner: CNRS-Montpellier